Image Added Image Added

The Value of User Research| Excerpt |

|---|

Image Removed Image Removed

Article 4 HeadlineBrian Flaherty | Reading time: about 12 minThis article is based on a research project conducted by NN/g PLACEHOLDER TEXT...

In 2021, Nielsen Norman Group (NN/g) — world leaders in research-based user experience — began a long-term research project to better understand human-centered design (HCD) and how practitioners utilize it in everyday work and its effects on project outcomes. NN/g began by establishing an HCD maturity model and realized that the maturity of individual team members and their experience, exposure, and mastery of HCD were essential to the overall team’s (or organization’s) ability to effectively utilize HCD methodologies. Catalysts were identified to help better understand the relationship between practitioner abilities and team performance. Catalysts consisted of individual practitioners whose HCD mastery positively influenced HCD practices in their teams or organizations. After conversations with the catalysts about their experience (and the experience of those they teach and guide), NN/g hypothesized that HCD practitioners share roughly the same learning journey, despite different backgrounds and contexts. NN/g began by conducting a large-scale survey of more than 1,000 practitioners and aimed at investigating respondents’ experience with HCD. Responses were classified into learning stages based on the self-reported HCD exposure, experience, primary activities, and biggest challenges. This process, combined with talking to hundreds of HCD practitioners each year at the NN/g user-experience conference, helped establish a set of unifying stages that most practitioners encounter while learning HCD. The stages include: newcomer, adopter, leader, and grandmaster. Imagine this—you’ve just landed a project where the client needs a redesign of their website and app. Client: “We’d like to improve the user experience. We want our customers to fall in love with our product—it has to be jaw-dropping!” Here’s the good news: At least this client is aware of user experience (UX), cares about their customers’ needs, and sees the value in investing in a great user experience. They’ve asked for an expert with UX skills to help… but do they really understand what it means to deliver an exceptional user experience? UX is more than following a collection of rules and heuristics in the product design process. As the name suggests, it is subjective—the experience that a person goes through while using a product. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the needs and goals of potential users, their tasks, and context, which are unique for each product.  Image Added Image Added

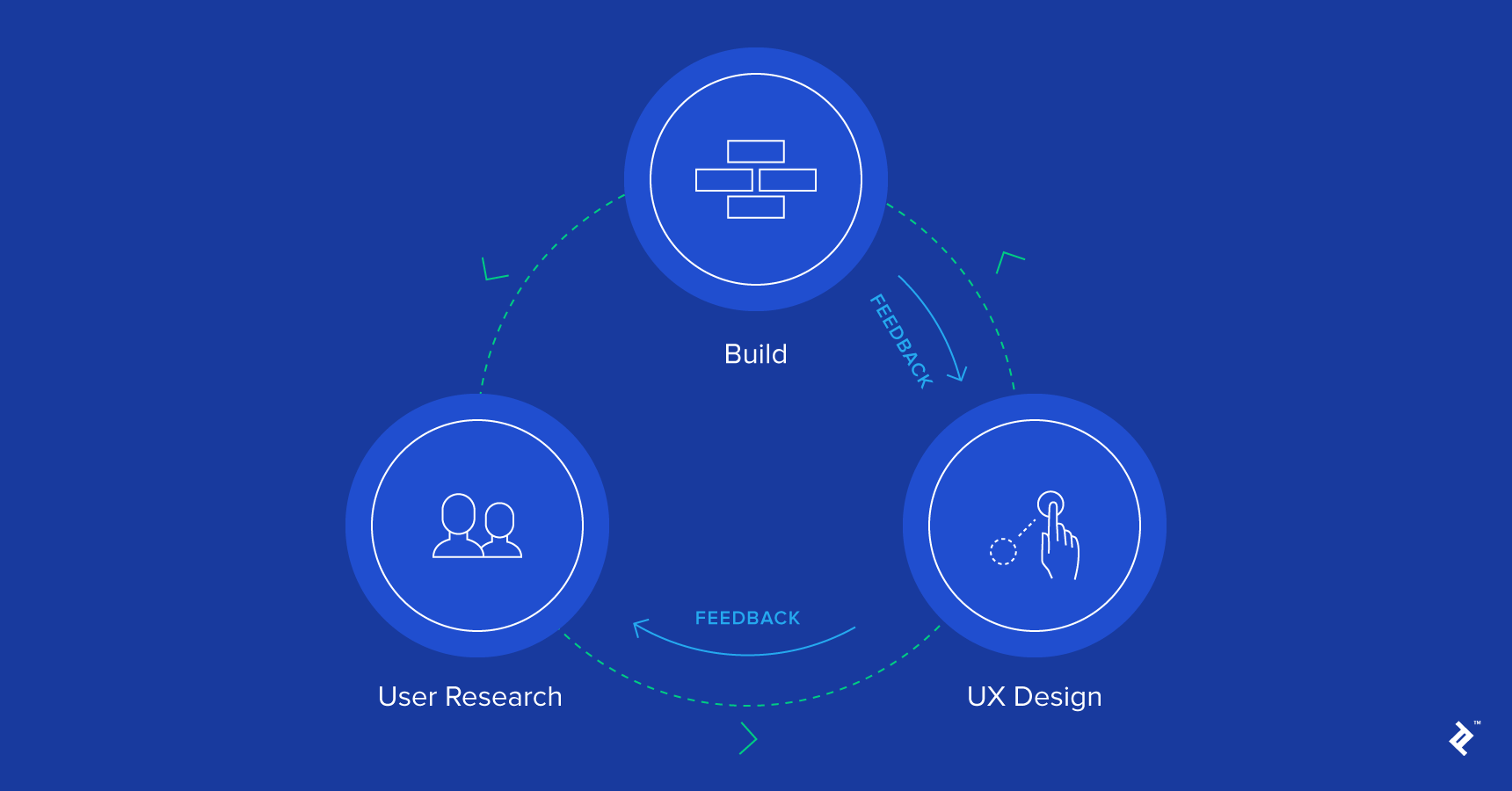

User research is a vital component of UX design. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

The UX expert will be familiar with the maxim, it all starts with knowing the user, but may very quickly discover that many clients have common misconceptions about UX. A UX expert knows that user experience research will help drive the redesign and usually begins by asking about the users: Who are they? What do they do? What do they want? What are some of their pain points? Unfortunately, not every client or stakeholder will immediately recognize the value of doing user research. What happens when their response is that they think it’s a waste of time and/or money? It’s the responsibility of UX specialists to educate and convince clients that good UX is next to impossible if it is not preceded by good user research. No Need for User Research? There Is Always a Need for User ResearchYou cannot create a great user experience without understanding target users or their needs. User research is one of the most essential components of user experience design.

Image Added Image Added

User research should shape your product design and define guidelines that will enable you to make the right UX decisions.

User research will help shape your product and define the guidelines for delivering a good experience for your users. By not spending any time on research and basing design decisions on assumptions, you risk not meeting your users’ needs effectively and efficiently. The UX expert should act as an advocate for effective design and never simply accept the argument that there is no time or money for user research. This is how senior UX architect Jim Ross of UXmatters sees it: Creating something without knowing users and their needs is a huge risk that often leads to a poorly designed solution and, ultimately, results in far higher costs and sometimes negative consequences.

Lack of User Research Can Lead to Negative ConsequencesWhat problem is the product trying to solve? When designing and refining a product, everything should lead back to the target user. Sometimes, even the worst ideas can seem great at first, especially when the deeper nuances of human behavior are not accounted for or tested against. Take Google Glass—originally released as a consumer gadget, the high-tech wearable failed to achieve widespread adoption. While the technical functionalities worked as expected, the lack of a clear user need and the device’s off-putting presence on the wearer’s face hint at anemic contextual user research. Skipping user research will often result in “featurities,” decisions that are driven by technical possibilities and not filtered by user goals. It’s the designer’s responsibility to validate every feature idea against the core use case. A great example of “featurette” design gone wild is the common television remote control. They are unintuitive and covered with more than a dozen buttons for which your average user has no clue as to their function, which results in annoyance and a frustrating user experience.

Image Added Image Added

Old remote controls are another example of hit and miss UX. There is little in the way of standardization, so each one takes time getting used to.

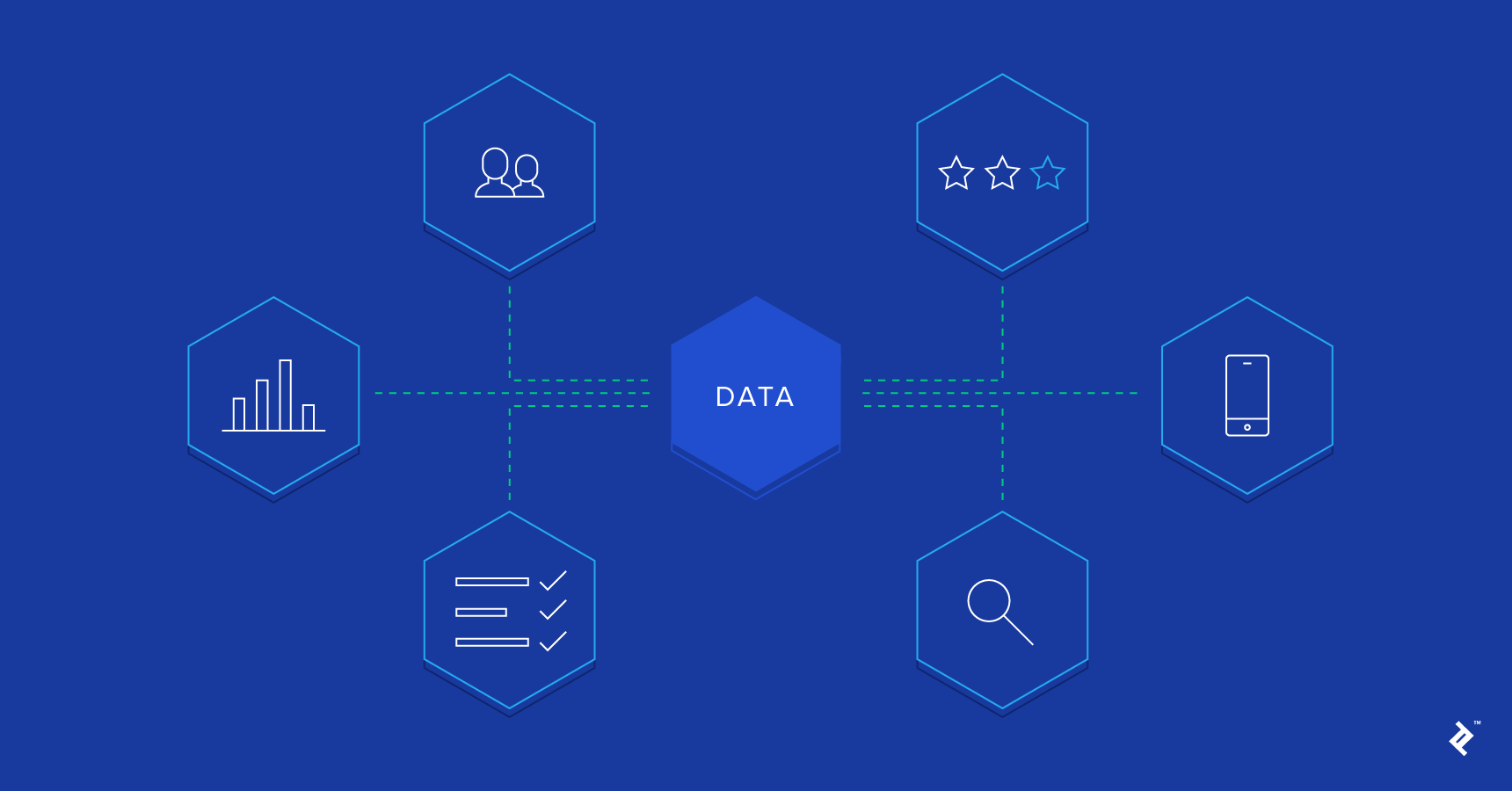

The same mistakes are often made in the digital world when the end user’s goals are not considered, understood, or designed for, such as frustrating user flows that add friction or confusion to the user’s experience or too many fields in a form that asks for too much information. Instead of encouraging habitual use through a quality user experience, poorly designed and implemented interfaces are more likely to scare off potential users—and the most effective way to understand your users is to conduct user research. The user research process will expand the timeline a little and its costs will vary, but both time and costs can be minimized. One option is to start with existing, easy to access sources of information about user behavior. Some of these methods may include: - Data analytics

- User reviews and ratings

- Customer support

- Market research

- Usability testing

Image Added Image Added

Quality user research requires time and resources. However, you can start by using existing information to get a sense of what your users need.

Whether you need to collect quantitative data or qualitative data will inform which type of research method to employ. It’s advisable to draw from more than one research method and synthesize the findings. Let’s take a closer look at some sources for existing information. Data AnalyticsIf you are working with an existing product, your client may have some data and insights about its use. User data analytics is a user research method designed to obtain a good overview about general product usage: how many visitors are coming to the website, what pages are most visited, how many people download the app and from which geo area, where visitors come from, when they leave, how much time they spend and where… and so on. By looking at user data analytics, a savvy researcher can begin to draw some conclusions about what users are doing—or not doing—and why. Looking at the abandon rate on sign-ups, for example, can point to a problem in the form design. Analyzing scroll-depth and navigation paths can hint at which content is most compelling to visitors.

Image Added Image Added

User data analytics give insights into how users find content, what they are looking at, and where they go next.

However, quantitative data can only paint part of the picture. It doesn’t tell you how the experience feels to a user, what users think about your service, or why they are spending time on your website. On its own, data analytics can tell you when a user leaves but may only partially hint at the reason. For example, the data indicates that users are spending a lot of time on a specific page. What it doesn’t explain is why. It might be because the content is compelling, which means users found what they were looking for. On the other hand, it could be an indication that users are looking for something they cannot find. Data analytics are a good starting point, but further qualitative data is needed in order to support the interpretation of the statistics. User Reviews and RatingsYour client’s product may have already received some user feedback. There might be a section for feedback or ratings on the website itself, and external sources may also be available. People might have talked about it in blog posts or discussion boards or may have given app reviews in an app store. Check different sources to get an idea of what users are saying. However, it’s important to be aware of the limitations when employing these kinds of qualitative research methods. People tend to leave reviews and ratings about negative experiences—don’t take this as a reason to shy away from user reviews or to ignore feedback. Instead, try to look for patterns in the responses and repeated themes in comments. Here are a few tips for making the most from user input: - Check whether any action has been taken on negative comments.

- Compare the timing of negative comments to releases and changelogs. Even great apps can suffer from poor updates, leading to a lot of negative comments in the days following the update.

- As much as possible, weed out baseless comments posted by trolls.

- What are users saying about the competition? Identify positive and negative differentiators.

- Don’t place too much trust in “professional and independent” reviews because they aren’t always very professional or independent.

User reviews are a good source for collecting information on recurring problems and frustrations, but they won’t give you an entirely objective view of what users think about your product. Customer SupportClients may have a customer support hotline or salespeople who are in touch with the user base already. This is a good resource to get a better understanding of what customers are struggling with, what kind of questions they have, and what features/functionality they are missing. Setting up a couple of quick interviews with call center agents and even shadowing some of their calls will allow you to collect helpful data without investing too much time or money. Conducting a focus group is also a great way to get a group of users to discuss and expand on the information gathered through customer support. Launching a survey is yet another inexpensive method for encouraging users to supply feedback.

Image Added Image Added

Customer interviews and focus groups are a great way to get actionable feedback from real users.

Customer support provides a good opportunity to learn about potential areas for improvement, but you will still have to dive deeper to get detailed information about a product’s intrinsic problems. Market ResearchThe client may have some basic information about the customer base, such as accurate demographic information or a good understanding of different market segments. This information is valuable in order to understand some of the factors behind a buying decision. By considering the information reported by market research, a UX expert can get a better picture of a variety of factors in user behaviors. This research helps pose questions around how the target user’s age or geographic location may factor into their understanding and use of a product. Market research is a good source of information for a better understanding of how the client thinks, what their marketing goals are, and what their market looks like. It should be considered alongside other user experience research in order to draw a conclusion. Usability TestingIf you are lucky, your client might have done some usability tests and gained insights about what users like or dislike about the product. This data will help you understand how people are using the product and what the current experience looks like. It is not quantitative research, and therefore you won’t get any numbers and statistics, but it helps you identify major problems and gives you a better understanding of how your user group interprets your interface.

Image Added Image Added

Usability tests help product teams understand and optimize user flows and user experience design.

One highly informative method for assessing a product’s usability is by conducting a heuristic analysis, although this might be a hard sell for some clients. Completing a task analysis exercise may be a lower overhead qualitative research methodology for usability testing. Activities like card sorting can help you understand how users organize and prioritize information. Conducting contextual interviews while watching a user navigate your product in the appropriate environment will help you gain valuable insight into their thought process. Usability tests are another good way of identifying key problem areas in a product. There is also the option to do some quick remote testing sessions by using services such as usertesting.com to gather data. How to Educate Your Client About the Value of User ResearchThe budget might be small and the timeline tight, but ignoring user research will eventually come back to haunt you. Help your clients avoid costly pitfalls by making them aware of the benefits of user research.

Image Added Image Added

What’s the ROI of good user experience? Knowledgeable UX experts must be able to communicate the value of user research to clients.

A client may insist that user research is not necessary because they are relying on, and trusting in, your skills as a UX expert. As a UX designer, you need to view user research as part of your toolkit, just like a craftsman’s hammer or saw. It helps you apply your expertise in practice, and just as a carpenter can’t work without a saw, you can’t do your job without your tools. No matter how much expertise you have as a designer, there are no generic solutions. UX design solutions always depend on the user group, the device, and the context of use, so it’s essential that they be defined and understood for every product respectively. You are the UX design expert, but you are not the user. User research helps to provide an unbiased view; to learn about the users’ natural language, their knowledge, mental models, and their life context.  Image Added Image Added

A great UX designer employs a variety user research methods and pulls data from a variety of sources.

Another argument against conducting user research is that the product will succeed by “following best practices.” Best practices originate from design decisions in a specific context, but the digital industry is evolving at a rapid pace. Design trends and best practice recommendations change constantly, and there is no fixed book of rules. Product designers need to be able to adjust and adapt to changes in trends, user behavior, and technology. Those decisions should be made based on user experience research, not solely on practices employed by others for different projects. Some clients or stakeholders may insist that they know all there is to know about their users, and therefore user research is unnecessary. However, without a clear picture of what the users are doing and why, a large piece of the puzzle is missing. Inviting your client to a user needs discovery session will help them observe how users are using their product. Start with small tests and use remote usability testing tools such as usertesting.com to get some quick insights and videos of users in action. Your client may be surprised at the results. The work product that comes from these exercises might be a user journey map or a user task flow. Aim for a visualized document that identifies unresolved questions so you can define areas that need more research.  Image Added Image Added

A UX designer maps out user flows and customer journey maps to understand what the user is experiencing.

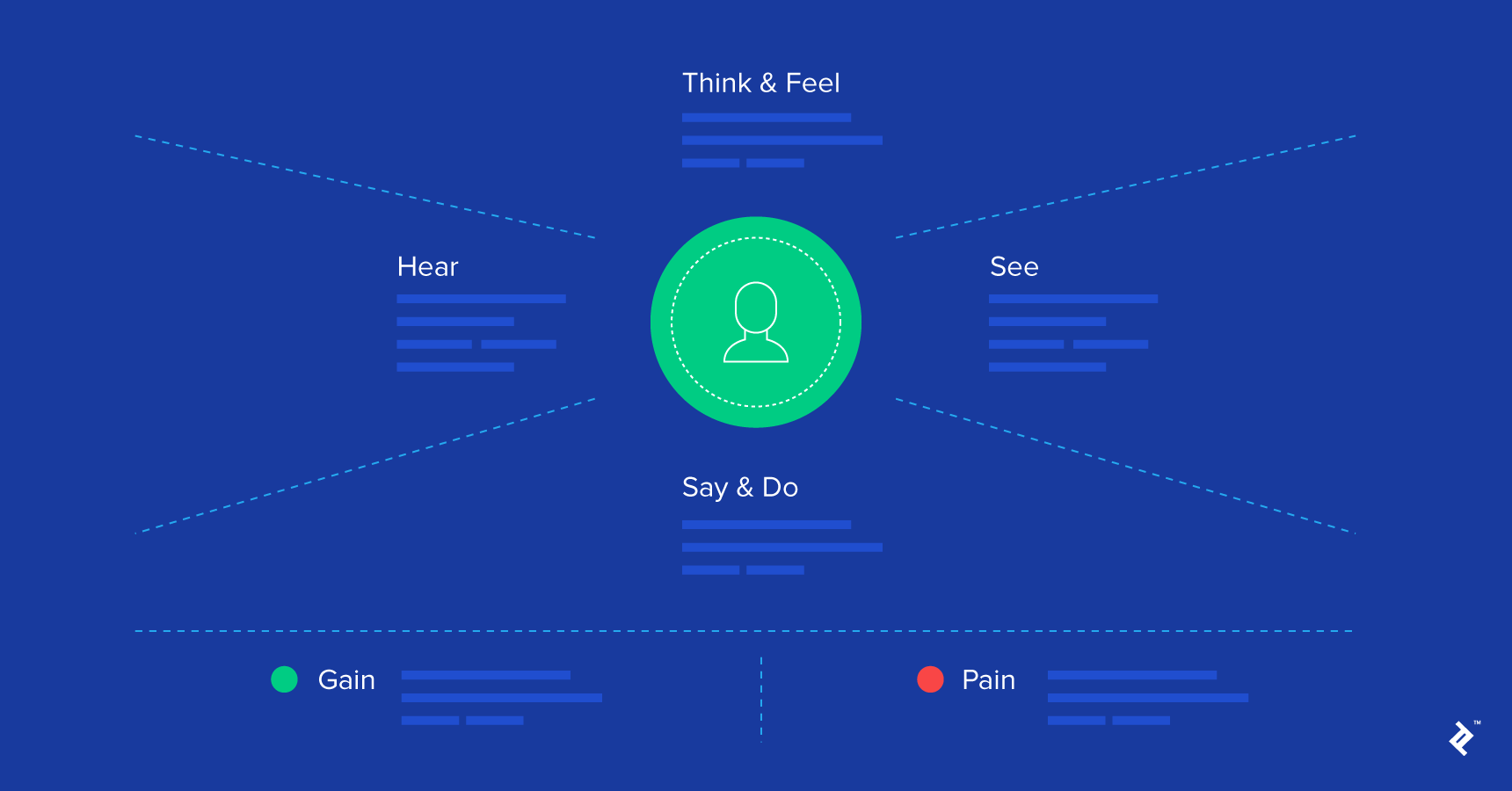

Some clients may point to personas as a stand-in for user research. Personas are a good tool for making a target user group more tangible and for surfacing needs, such as building key user task flows and how that might vary for different groups. But personas are intended for identifying a target user base and to help the product team gain empathy for the user. Personas will help you understand who the users of the product are but not how they will use the product. They will outline certain attributes, behaviors and motivations, goals, and needs but will not give the UX researcher habits, culture, or social context.

| Panel |

|---|

|

| Column |

|---|

|  Image Added Image Added |

| Column |

|---|

|  Image Added Image Added

|

| Column |

|---|

| Frauke Seewald

Frauke is a senior UX designer with a background in psychology and a focus on user research (understanding the target group, their needs, and current behavior), information architecture (structuring content and processes), and interactive wireframes. She is a strong team player and has a very organized work style |

|

Why these stages matterHCD practitioners can better understand their own learning process and set appropriate expectations if they know the typical stages of the learning journey. NN/g concluded that: - Most learning journeys feel frustrating at some point. Having insight into the HCD learning journey and the end goal can provide encouragement during “what’s the point” moments. If you’re learning HCD independently, awareness of the journey can help you feel less alone.

- Identifying one’s current phase can help predict future progress, staying focused on the goals of the current learning phase rather than jumping ahead. Jumping ahead runs the risk of creating experiences that may be confusing, and thus less motivated to continue to learn.

Course facilitators (or managers or mentors), must empathize, create an effective HCD learning experience for others, and enable sustainable, long-term success. - Understanding that different people will be at different stages in the learning process is a key part in being an effective educator. It allows for the delivery of effective learning experiences without overwhelming the audience with too much complexity and also preemptively mitigate learners’ pain points at each phase.

Educating and activating a group of people takes a lot of resources (time, money, and effort). The education process should be intentionally designed, in order to maximize resources and return on investment. Mapping participants’ phases and their progression through the learning journey allows an educator to benchmark progress, and indirectly, success of the training. As practitioners progress through the stages, their mastery increases in a nonlinear fashion — experiencing fluctuations due to various factors, especially, lack of self-confidence. Note that mastery is a combination of competence and confidence; both are required to effectively use HCD. If a practitioner is good but still feels insecure, they won’t deviate from the strict steps of HCD and won’t teach others. The goal is to create alignment between competence and confidence in order to master HCD. The StructureRather than thinking of each phase as a discrete checklist, NN/g created a three-component framework for characterizing each learning stage: criteria, primary activities, and educator goals. - Criteria are observable qualities that can help the learner (or an external observer, such as a trainer) identify the learner’s current stage along the learning journey. It includes awareness of one’s own competence, level of exposure, and confidence.

- Primary activities are the learner’s actions and use of HCD methodologies.

- Educator goals and obstacles summarize learner’s pain points at any given stage and corresponding educator goals that can help learners overcome them.

Phase 1: Newcomer This phase is the first in the learning journey. For the majority of HCD practitioners, this exposure occurs via a university or institution, a place of work, or an online resource. The amount of time spent at this first stage depends on how motivated the learner is. Interestingly, many practitioners immediately perceive HCD as useless and never leave this stage. Criteria Individuals in this stage have been introduced to HCD, but have limited experience with it. Practitioners in this phase fall into 2 buckets: - Individuals who are committed to learn HCD

- Individuals who are not interested to learn more about HCD. They’ve been exposed to it, but that is where their learning journey halts. Newcomers may remain in this stage indefinitely until they encounter a deeper exposure to HCD that broadens their perspective, experience, or acceptance.

Newcomers’ knowledge is minimal; they have a surface-level understanding of HCD, often rooted in the definition they received during their first exposure. They may be able to provide a definition, but are not familiar with the details of a framework or its value. They have topical associations with HCD — sticky-notes, phase models, and whiteboards. Newcomers are unaware of their HCD incompetence. In other words, they don’t yet know what they don’t know. Primary Activities Newcomers’ primary goal is to understand the basics — what HCD is and why it’s useful. Often, this stage’s activities are self-initiated: browsing articles, reading books, or signing up for a course. In other cases, HCD is learned by necessity or requirement at work or school through onboarding programs, collaborative workshops, required courses, or mandated trainings. Most newcomers have not yet actively practiced HCD activities. If they have practiced HCD at all, their participation is limited and surface-level. Educator’s Goals and Obstacles The goal of an HCD educator at this stage is to communicate the purpose and potential value of HCD and to motivate the newcomer to pursue learning, then make time for it and move on to the next phases. Common obstacles are overcoming learners’ negative sentiments: annoyance with “yet another thing to learn,” unsuccessful previous attempts or experiences, capped bandwidth, and realization of their own limits (in this case, how little they know about HCD). Phase 2: AdopterIndividuals in phase 2 have adopted HCD and begun to practice it. They may have had some ups and downs in their limited experience with HCD. It is common for adopters to flip-flop between overconfidence and self-doubt and to feel both confused and successful at the same time. Successful adopters have discovered how relevant HCD is to their work or life and, thus, make a commitment to continue learning. Criteria Increased (passive or active) exposure and familiarity with HCD has made adopters aware of their knowledge limits. They understand the potential of HCD, but still have a lot to learn. Adopters have invested time, effort, and energy into HCD and have started applying it to their work with mixed success. The commitment to HCD at this phase can be self-initiated or dictated by an authority with an invested interest (leadership, organization, or supervisor). Primary Activities Adopters practice HCD in a linear way — by the book. They rely heavily on checklists — for example an HCD Phases Model, as well as for the activities associated with each of its steps. Many adopters lean towards a prescribed, branded version of HCD, often provided by their institution, company, or a reputable external organization. It is common for HCD practitioners to encounter failure in this phase — especially if they are learning predominately on their own — because of their incomplete understanding of the HCD framework. Common types of failure include jumping to conclusions, using the wrong activity at the wrong time, and lack of buy-in or support from others. These failures push some practitioners to abandon HCD altogether. However, most learning in this phase occurs through failure. Practitioners who embrace failure tend to develop a better understanding of HCD in future phases. Some adopters might learn primarily by actively participating in HCD training, coaching and activities together with experienced HCD practitioners. While this group of adopters may not have the opportunity to experience a sense of failure because of the support received from their peers, it is still likely they will question the value and legitimacy of HCD from time-to-time. Educator’s Goals and Obstacles Adopters are on the bike, but still need training wheels and coaching. Adopters’ confidence drops as they realize the indirect ways in which HCD can be applied and how much they have to learn — for example, how straightforward they originally thought the process was versus how abstract (and potentially overwhelming) it really is. The goal of the educator at this stage is to help learners through hands-on practice and assistance until they can comfortably use HCD on their own. Many individuals can become confused in this phase when they cannot make a direct connection to the relevance of HCD. Thus, it is imperative that adopters find relevance and application to their everyday work. Phase 3: Leader This is the proficiency stage of HCD. Leaders can articulate HCD succinctly to others, steadily growing their confidence, with varied experiences and continued exposure. Leaders take an active, independent role in their learning journey and begin to think adaptively about HCD; starting to explore new applications and may even have established a reputation as a subject matter expert. Criteria Leaders practice HCD with general ease, confidence, and independence. Leaders become more and more aware of their new knowledge and comfort as they mature through this phase. They often teach others earlier in the learning journey. They are able to consistently and somewhat adaptively perform HCD activities without thinking too much about them. Leaders don’t try to apply HCD by the book, rather use it as needed depending on the goals. Primary Activities HCD practitioners in this phase lead HCD activities with others or perform HCD without coaching, but still apply preparation and focus. While they were previously participants, they now facilitate, initiate, and even advocate for collaborative HCD activities. Activities that leaders are involved in gradually increase in complexity, ranging from involving users in learning opportunities to fostering stakeholders into the process and prototyping. Educator’s Goals and Obstacles The goal of the educator in this phase is to continue to instill confidence and help sustain learner commitment. The goal should be to empower leaders to transition into the role of HCD educators and facilitators. As much as they’ve progressed, they still may not be aware of weaknesses or potential improvements (even though they often recognize a mistake after they made it). Promoting reflection in this phase is the key to helping leaders continue to grow (and progress to grandmasters). They must take an active role in adapting the HCD practice to fit their contextual goals and needs, be sustainable over time, and maximize potential benefits. Phase 4: GrandmasterIf you are familiar with the game of chess, the title of grandmaster is only given to the most exceptional players—those who have spent countless hours perfecting their skills and techniques. HCD practitioners at this stage have not only become teachers of HCD, but create new ways of applying it, thinking about it, and adding to it. The practice of HCD is so embodied in their behavior that they seldom have to think about applying it. Grandmasters view HCD as a flexible, dynamic toolkit. They’ve long departed from the concept of a prescribed process and rather view it as scaffolding to solve both organizational (often internal) and end-user (external, product-related) problems. However, this phase doesn’t come without downsides. Grandmasters are more likely to doubt HCD than leaders, often when early-stage learners fall victim to mismanaged HCD marketing and thus misinterpret, misapply, or undercut the practice as a whole. Criteria Grandmasters’ defining characteristic is the ability to critically reflect on their HCD practice. This enables them to judge what is useful and potentially depart from the traditional ways and activities of HCD. Grandmasters also know how to help others to this same stage of enlightenment. Grandmasters are aware of their competence. They have an in-depth, intuitive understanding and can blend HCD skills together to meet specific needs. Primary Activities Traditional HCD activities are still used by grandmasters, but are altered, adapted, and applied in complex ways, depending on the goal, audience, and potential obstacles. Grandmasters don’t stick to prescribed or branded versions of HCD and more often pull tools and/or activities from other realms, like service design and business strategy. While basic HCD activities are still carried out in this phase, they differ from those in earlier stages because they are inputs or alignment strategies for more complex, involved activities (compared to previous stages where the basic activities are the end goal). Educator’s Goals and Obstacle Grandmasters have very likely surpassed their original teachers. Their goal becomes not just activating and educating individual learners, but rather organizations as a whole. As practitioners themselves, grandmasters face an increasing likelihood of (re)questioning the value of HCD. Increased knowledge and mastery are a blessing and curse; this pessimistic view is often rooted in the realization of what HCD can and cannot solve (contrary to earlier naive ideas that HCD can be a cure-all). However, even grandmasters can get better, by self-reflection, by learning from their peers, and also by learning from their juniors: one of the skills of supreme mastery is the ability to discern which of the hundreds of ideas generated by eager newcomers is actually a stroke of genius. Other Considerations - Trained designers experience the HCD learning journey too, just differently. Many designers view HCD as simply a way to articulate and communicate a creative approach to problem solving. Thus, many designers are likely to feel as if they bypassed this learning journey altogether because this is how they instinctively think. However, designers experience this learning journey too, albeit much earlier in their education or career, and likely not packaged or branded as HCD. This does not mean that all grandmasters are designers, but rather that many successful designers likely are.

- Individual practitioners can be at multiple levels at the same time. Some skills may fall into one phase, while others into a lower different phase. For example, a practitioner’s mindset and reflection may fall into Grandmaster, while their hands-on experience and exposure to activities into Leader. The goal is to identify this imbalance and invest in experiences that bolster weaker dimensions of our practice.

The HCD learning journey is a high-level, distilled representation of the most common learning phases observed in the NN/g research. Learning and teaching HCD is messy; not all experiences will fit squarely into this model. Regardless, it is imperative to frame and articulate learning HCD as an experiential journey. Doing so can help all practitioners become more effective learners and educators. Learners can gain insight and awareness into the greater journey and goals, while educators can thoughtfully and successfully execute the HCD learning experience they aim to create.  Image Removed Image Removed

This article is based on a research study conducted by the Nielsen Norman Group. Originally published January 2021. | Panel |

|---|

| | Anchor |

|---|

| BriBio | BriBio | | Column |

|---|

|  Image Removed Image Removed |

| Column |

|---|

|  Image Removed Image Removed

|

| Column |

|---|

| Brian Flaherty

Brian is currently a Senior Design Strategist with the Human-Centered Design Center of Excellence (HCD CoE). Brian has been a graphic designer for more than 25 years, and has been practicing human-centered design for at least 13. Prior to joining Tantus as an HCD Strategist, Brian spent 12 years as a Creative Director, Communications Supervisor, and HCD Practitioner at Johns Hopkins University supporting classified and unclassified communications, primarily for the Department of Defense. Brian holds a BA degree from the University of Pittsburgh where he majored in Creative Writing and Public Relations. Brian is happily married, has a daughter just about ready to begin college, and considers two cats, two dogs, 26 chickens, three ducks, a crested gecko, and a ball python named Noodles his step children. |

|